Coating method could improve temporary implants that dissolve in the body

Very even, pure coatings that promote healing may now be possible for biodegradable sutures and bone screws.

Very even, pure coatings that promote healing may now be possible for biodegradable sutures and bone screws.

A strategy for coating complicated surfaces with biodegradable polymers has been pioneered by a team of researchers led by Joerg Lahann, a professor of chemical engineering and director of the Biointerfaces Institute at U-M. It could enable coatings for implants that dissolve in the body, such as drugs to improve healing.

Permanent polymer coatings are already used on medical equipment that does not biodegrade, such as metal stents that hold blocked arteries open. The drug prevents cells from growing over the webbed metal structure and narrowing the artery again. It can be applied with a technique called chemical vapor deposition – a process that puts the drug into a gas phase and lays it down in an even coating, like fog turning into frost.

“What you couldn’t do until we published this paper is take a suture that biodegrades and coat with a vapor-based coating that would provide similar benefits,” said Lahann. A suture or a biodegradable bone screw might benefit from a coating of growth factors to promote healing, he added.

Other ways of coating include dissolving the drug into a solvent and then spraying it onto the structure. However, the solvents are often toxic, and the spray technique can bridge gaps in open structures or result in one part of a structure blocking the spray from reaching another.

Still, chemical vapor deposition is very tricky with polymers, or chemicals built in a chain – and a biodegradable coating would need to be made out of polymers. Polymers tend to break up when they are vaporized, so they must be built piece by piece onto a surface.

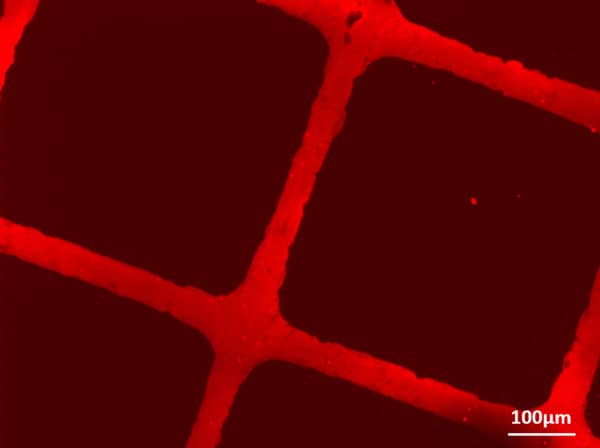

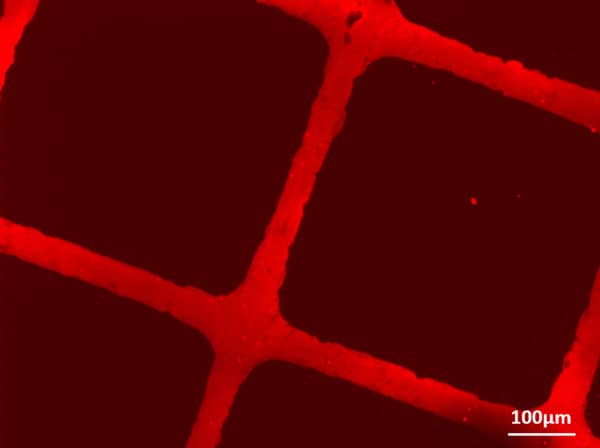

The researchers demonstrated this using two different monomers, or types of links in the polymer chain. By controlling the ratio between the two monomers, and the chemical groups hanging off the sides of the monomers, the team could control how quickly water could get into the polymer and begin breaking up the chain into its nontoxic elements.

In the lab, Lahann’s group is testing out the coating technique with biodegradable scaffolds that they use for implanting stem cells to help heal wounds involving gaps in tissue. They are also beginning a project with the lab of William Giannobile, the Najjar Professor of Dentistry and Biomedical Engineering, to coat biodegradable dental implants with growth factors to speed healing.

Other members of the research team hailed from Northwestern Polytechnical University in Xi’an, China, and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany.

The study was funded the German Science Foundation under the SFB grant 1176 and the Army Research Office (ARO) under Grant W911NF-11-1-0251.

Lahann is also a professor of biomedical engineering, macromolecular science and engineering, and materials science and engineering.