A systems thinking approach to biology and diversity

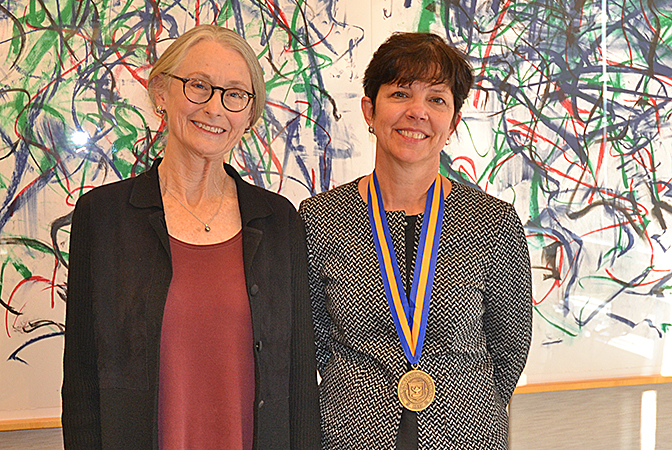

U-M ChE’s Jennifer Linderman appointed the Pamela Raymond Collegiate Professor of Engineering.

U-M ChE’s Jennifer Linderman appointed the Pamela Raymond Collegiate Professor of Engineering.

When Jennifer Linderman was selected to receive a Collegiate Professorship in 2020, she decided to honor Pamela Raymond, Stephen S. Easter Collegiate Professor Emerita in the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology. Although Linderman and Raymond work in different areas of biology, both are concerned with multi-scale processes, cell signaling and self-organizing structures.

Dr. Raymond’s work to improve opportunities for women and underrepresented minorities encouraged Linderman to pursue her interests in diversity and academic leadership and helped her shape her career at Michigan. Raymond served as vice-provost for academic and faculty affairs from 1997-2002, where she gave early support to ADVANCE, a program focused on faculty diversity and excellence that Linderman now directs.

“Pamela has encouraged me, by example and in words, to pursue my interests in diversity and academic leadership, and this has profoundly influenced my career here at Michigan,” said Linderman.

“I first met Jennifer when she became a member of ADVANCE’s STRIDE committee, which offers workshops for faculty search committees to promote equity in faculty recruitment,” said Raymond. “To prepare and develop these workshops, the members of the STRIDE committee read and discussed the social science literature that addresses diversity and inclusion. For me, and later for Jennifer, preparing and developing workshops for STRIDE was a transformational experience—confronting the research data and concepts about human behavior and social organizations that explain the persistence of white male dominance in the academy.”

Raymond considers she and Linderman “academic sisters and soulmates.” “We both trained in our respective fields of science and technology, and studiously immersed ourselves in that academic world and culture as we developed our own research programs and scholarly pursuits. But then we encountered the ADVANCE program, and our lives were transformed.”

Linderman has been on the faculty of the Chemical Engineering department since 1988. Her research interests are in systems biology, with a focus on quantitative systems pharmacology, immunology, cell signaling, cancer, tuberculosis and computational modeling.

As a young researcher, she became interested in systems biology, a discipline that studies the simultaneous molecular and cellular interactions and physical processes that occur in biology. Much of biology is reductionist—focusing on one molecule or one interaction. Systems biologists are more interested in the larger picture and want to find out how the whole system is put together—how all the parts and processes work together to produce an outcome, and for Linderman, with the goal of improving human health.

“Many of the principles that we apply in our computational modeling here come straight out of chemical engineering—transport and reaction.”

Jennifer Linderman

Pamela Raymond Collegiate Professor of Engineering and Director of the ADVANCE Program

Linderman’s collegiate professorship was marked in a ceremony on October 26, where she delivered a lecture on “Tuberculosis—the other pandemic—and how engineering can improve treatment.” Until the outbreak of COVID-19, tuberculosis was the infectious disease responsible for the most deaths each year, approximately 1.5 million. “There are fundamental and vitally important questions about tuberculosis that we can approach with tools from systems biology, especially computational modeling,” said Linderman.

“There are a myriad of immune processes going on that play out differently in individuals, so we work to understand why some people get latent disease and others get active tuberculosis. And although there are antibiotics against the bacterium, they may not be present in lung lesions at sufficient concentrations and for sufficient amounts of time, or they may be less effective against some bacterial states or drug-resistant bacteria. Many of the principles that we apply in our computational modeling here come straight out of chemical engineering—transport and reaction.”

Tuberculosis is not the only disease for which Linderman is applying computational systems biology to improve treatment. Together with her department colleagues, Greg Thurber and Pete Tessier, she is working to discover new ways to treat cancer with antibody drug conjugates (ADCs). ADCs are a rapidly growing class of biological drugs that are designed to target and kill only tumor cells and leave healthy cells alone.

“For years, the field of ADCs struggled in the clinic, where assembling the ‘best’ antibody with the ‘best’ payload and ‘best’ linker didn’t lead to effective results,” explained Thurber. “However, by considering the entire system together, ADCs can be designed for a particular type of cancer, and this aligns perfectly with Professor Linderman’s approach. By simulating the tumor environment and all aspects of the drug, her systems biology methods can quickly sift through thousands of different scenarios to pick out the candidates that will be most successful. Her work has provided a lot of clarity to the field, helping to highlight why the recent wave of FDA-approved ADCs is so successful for patients and how we can design the next wave.”

Interest in computational modeling in biology has exploded in recent years, as university researchers and drug companies find that computational studies can be used to identify and test new hypotheses, guide laboratory experiments and clinical trials, and save money. Many of Linderman’s students now work in quantitative systems pharmacology positions in industry or pursue these ideas in academic positions.

Before being named the director of the University of Michigan’s ADVANCE program in 2016, Linderman served as associate dean for graduate education in the College of Engineering from 2014-2016.

“Jennifer has been deeply influential in the College of Engineering and across the university. In her role as associate dean in the college, she was deeply committed to the success of graduate students. Now, as director of ADVANCE, she is leading discussions across campus about how best to support our diverse faculty.”

Michael Solomon

Dean, Rackham School of Graduate Studies and Vice Provost for Academic Affairs, Graduate Studies

“In addition to her many research and teaching accomplishments, Jennifer has been deeply influential in the College of Engineering and across the university. In her role as associate dean in the college, she was deeply committed to the success of graduate students. Now, as director of ADVANCE, she is leading discussions across campus about how best to support our diverse faculty from the very first day they arrive here to pursue their careers,” said Michael Solomon, Dean, Rackham School of Graduate Studies; Vice Provost for Academic Affairs, Graduate Studies; and Professor of Chemical Engineering.

Linderman was the first woman faculty member hired by the Department of Chemical Engineering, and she joined U–M at a time when women comprised only 4% of the faculty in the entire College of Engineering, and there were even fewer underrepresented minority faculty. Often, it wasn’t a great environment for these new faculty to start their careers.

As with her research, Linderman is interested in pursuing “systems-level” change in her DEI work. “What processes and practices can we change or newly implement to improve faculty equity?” she said. “Experience has shown me that if you improve hiring practices, retention, and workplace climate with an eye toward those who are underrepresented, you often improve it for all faculty. For example, if we make our practices more transparent, have robust mechanisms for mentoring, mitigate biases in faculty hiring, and support developing leaders, these are changes that will ultimately help everybody.”

In appreciation of her diversity, equity, inclusion, and mentoring efforts, she received the Harold R. Johnson Diversity Service Award in 2016, the Rackham Distinguished Graduate Mentor Award in 2017, and the Women’s Initiatives Committee Mentorship Excellence Award from the American Institute of Chemical Engineers in 2019.

As Sharon Glotzer, Anthony C. Lembke Department Chair of Chemical Engineering, said at Linderman’s professorship ceremony, “Recognition of Jennifer’s many contributions with a collegiate professorship is a well-earned one. Jennifer has consistently demonstrated outstanding achievements in scholarly research and creative endeavors, she’s amassed a record of sustained excellence in teaching and mentoring of students and junior colleagues, and, through service and other professional activities, brought distinction to herself, the department, and the university.”

Linderman is also a professor of biomedical engineering. She received her BS in chemical engineering from the University of Rochester and her MSE and PhD in chemical and biomedical engineering from the University of Pennsylvania, and did postdoctoral work at the University of Massachusetts.