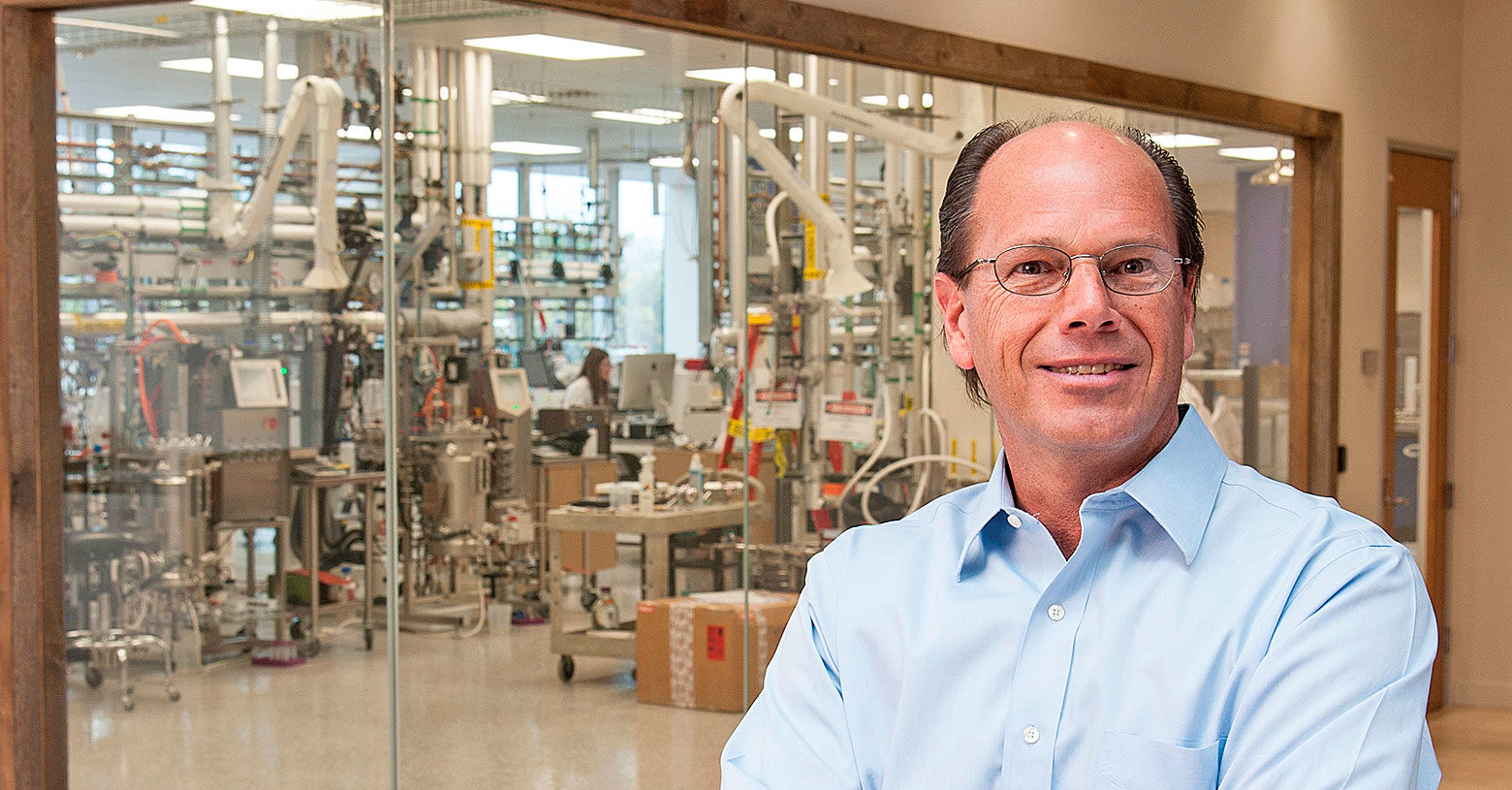

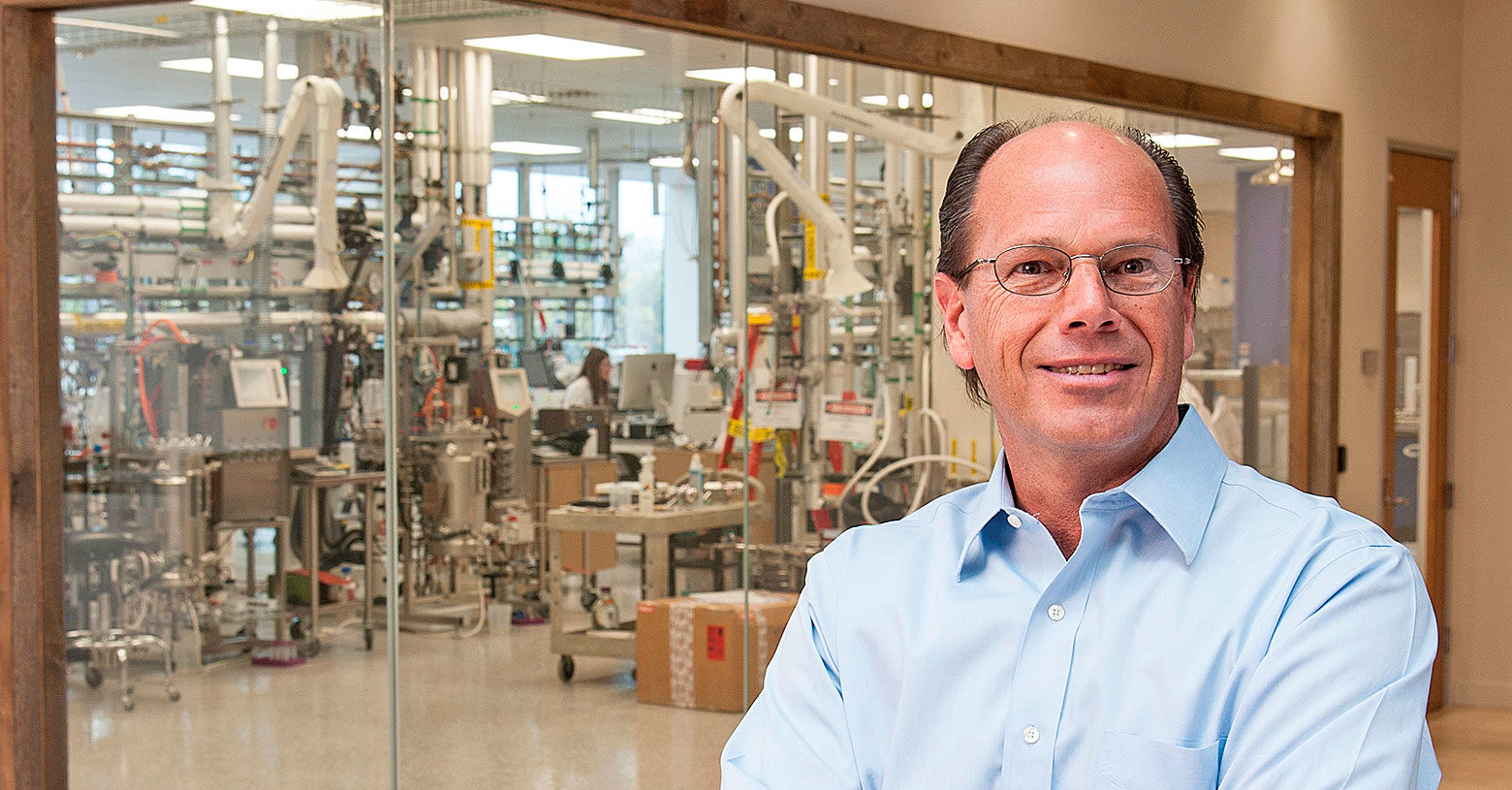

Jeff Lievense receives the 2022 ChE Alumni Merit Award

U-M ChE alum, member of the National Academy of Engineering, and External Advisory Board member, Jeff Lievense, is the recipient of the 2022 alumni merit award.

U-M ChE alum, member of the National Academy of Engineering, and External Advisory Board member, Jeff Lievense, is the recipient of the 2022 alumni merit award.

First published in 2019 and written by Sandy Swisher.

Jeff Lievense (BSE ’76), a recent inductee into the National Academy of Engineering, is convinced that the University of Michigan’s chemical engineering program defined his professional career.

From inspiring him to develop more sustainable, bio-based methods for producing chemicals to providing world-class interdisciplinary training to act on his passion, U-M Chemical Engineering instilled in him the work ethic to make it happen.

Jeff grew up in Holland, a small, conservative town in western Michigan, where he was a conscientious student from a lower-income family. When he started his college applications, Jeff narrowed his focus to in-state public schools, first visiting Michigan State University, then U-M. After that, there was no question where he wanted to go—U-M.

Once on campus, a collection of experiences and global developments led him from pursuing fisheries management like his Uncle Stanley, also a U-M alumnus, to declaring a more unusual major: chemical engineering.

Given Jeff’s strong aversion to high school chemistry, chemical engineering seemed like a peculiar choice. However, then-Professor David Dull’s freshman chemistry course completely changed Jeff’s attitude and his career trajectory.

Jeff’s chemistry and calculus classroom experiences—combined with his growing awareness of pressing environmental challenges and the 1973 oil crisis that resulted from Arab oil producers halting exports to the U.S.—convinced him to switch to a special program in chemical engineering. In the new bio option, Jeff saw a career path where he could help alleviate global challenges in food, health, energy, and the environment.

While then-ChE professors Lloyd Kempe and Fred Bader encouraged Jeff’s interest in biochemical engineering, Professor Scott Fogler taught Jeff an important lesson in attentiveness. While sitting in the back of an East Engineering classroom, doodling in his notebook, Jeff heard his name called. Jeff hesitated, having no idea how to respond to Fogler’s question, and Fogler directed the question to another student. Jeff relaxed, but redirected his attention from his notebook to Fogler’s lecture. A few minutes later, Fogler called Jeff’s name again.

This time, Jeff was ready.

Jeff recalls Ann Arbor in the early 1970s as “a crazy place.” He says he and his friends worked hard and played hard during their undergraduate years. The legal drinking age had been reduced to 18 and marijuana possession was decriminalized in Ann Arbor.

“There was an ‘anything goes’ mood in the dorms, frat houses, around town, and even in the football stadium stands,” he remembers. “The Rainbow People’s Party sponsored a beer bash and concert by Mitch Rider and the Detroit Wheels in my dorm’s cafeteria. Hair was long—including mine—and music was diverse and amazing, rock, blues, Motown, jazz, and folk from that era are still my favorites.”

At Michigan, Jeff encountered people and ideas that he was unaccustomed to.

“I was exposed to diverse ethnicities, ways of thinking, lifestyles, foods, you name it. And so many smart people,” Jeff remembers. “It was my introduction to the world. From all of this, I learned to be open-minded; to gravitate toward challenges; and, of course, to work very hard.”

Through hard work, Jeff achieved more than he thought possible during his undergraduate courses, and his competitive spirit and work ethic carried over to his graduate studies and his professional career. Jeff gravitated toward bigger challenges, often first-of-a-kind projects, and gave his all in tackling them.

When he completed his BSE degree, Jeff’s U-M professors encouraged him to pursue graduate studies outside U-M to broaden his ChE education. Jeff chose Purdue University for its large biochemical engineering program. His doctoral research combined fermentation experiments, metabolic modeling, and real-time computer applications. As a graduate student, he met current U-M ChE Professor Henry Wang, who was then a “spirited” fellow biochemical engineering graduate student at MIT.

Jeff started his career at Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York, in 1982. While here, he began developing industrial fermentation-based processes for making all kinds of things, such as: enzymes for clinical diagnostic applications; amino acids as animal nutrition supplements; and the denim dye indigo. He was introduced to genetic engineering of microbes and recognized the potential to benefit society through its application—both by enabling the replacement of petrochemicals with more sustainably-sourced versions and introducing entirely new chemicals that could not otherwise be made.

In 1990, Kodak’s Bio-Products Division was spun out into a new biotech company called Genencor International. Jeff explored more cutting-edge biological technologies and learned about life in a multi-cultural company. After three years, Genencor transferred his metabolic engineering group to San Francisco. Jeff and his wife had young children and decided against the long-distance move, instead taking a job close to family in Lansing, Mich., as Vice President for Research & Operations with Michigan Biotechnology Institute (MBI). Unfortunately, MBI didn’t have much money. In this position, he learned how to deliver difficult news to employees during challenging situations and to rigorously manage an organization’s finances.

After logging long hours at MBI, Jeff sought a company where he could maintain a healthier work-life balance and stay true to his professional vision. He accepted a position with A.E. Staley Manufacturing Company in Decatur, Illinois, a major U.S. corn processor that was absorbed in 1988 by Tate & Lyle, a British public company. Jeff built the company’s R&D program from scratch, developing technologies to produce chemicals by fermentation using the company’s abundant, low-cost corn starch as the feedstock.

During Jeff’s 13-year tenure, Tate & Lyle became a major producer of citric acid, a versatile food and industrial ingredient. Jeff learned to focus R&D on delivering practical, meaningful improvements to manufacturing plants on three different continents. In another major program, together with DuPont, his company developed and commercialized a first-of-its-kind fermentation process for 1,3-propanediol (PDO) using a genetically engineered bacterium and at a lower cost than competing petrochemical routes. PDO is a chemical used in making a novel polymer with superior properties in carpeting and apparel.

I am most proud of my contributions to first-of-a-kind developments that will have a lasting impact on the industrial bioengineering sector and the positive influence I’ve had on many younger people in the field.

Jeff Lievense

In 2007, Amyris, a Berkeley, California, start-up, approached him with a compelling proposition—to lead its embryonic process technology group in developing first-of-its-kind fermentation technologies for producing a class of natural products called terpenes. Over the next five years, Amyris succeeded in commercializing two terpene products, one a key ingredient in malaria treatment (artemisinic acid) and the other a versatile biofuel and chemical intermediate (farnesene). Along the way, Jeff learned to thrive in a true start-up company operating at a frenetic pace and also helped navigate the process of taking a company public.

In 2012, he made his final career move to Genomatica, where he served as Executive Vice President of Process Technology. This was an exciting role, given the company’s aspirations to replace established industrial intermediate petrochemicals with more sustainably sourced versions made by fermentation. His process leadership skills were immediately put to use in planning for and executing the scale-up of Genomatica’s fermentation process for 1,4-butanediol, an industrial chemical with a $4 billion per year world market. This was another first-of-its-kind success: a fermentation chemical competing head-to-head with the entrenched petrochemical. Today, Genomatica is a leading bioengineering provider to the global chemical industry.

Jeff retired at the end of 2018 and continues to serve as a consultant in industrial bioengineering. Reflecting on his career, he says, “I am most proud of my contributions to first-of-a-kind developments that will have a lasting impact on the industrial bioengineering sector and the positive influence I’ve had on many younger people in the field by sharing my expertise in the workplace and through a UC San Diego short course that I led for several years.”

Last spring, after nearly four decades in industrial bioengineering, Jeff Lievense was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering (NAE). He was recognized for his “leadership in biomanufacturing of sustainable chemicals.” He was one of 86 new members from the United States this year, including also ChE Chair Sharon Glotzer and Engineering Dean Alec Gallimore. All were formally inducted during a ceremony at the NAE’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C., on October 6, 2019.