Nanotechnology: Theory predicts new type of bond that assembles nanoparticle crystals

Turns out entropy binds nanoparticles a lot like electrons bind chemical crystals.

Turns out entropy binds nanoparticles a lot like electrons bind chemical crystals.

EXPERTS:

Entropy, a physical property often explained as “disorder,” is revealed as a creator of order with a new bonding theory developed at the University of Michigan and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Engineers dream of using nanoparticles to build designer materials, and the new theory can help guide efforts to make nanoparticles assemble into useful structures. The theory explains earlier results exploring the formation of crystal structures by space-restricted nanoparticles, enabling entropy to be quantified and harnessed in future efforts.

And curiously, the set of equations that govern nanoparticle interactions due to entropy mirror those that describe chemical bonding. Sharon Glotzer, the Anthony C. Lembke Department Chair of Chemical Engineering, and Thi Vo, a postdoctoral researcher in chemical engineering, answered some questions about their new theory.

What is entropic bonding?

Glotzer: Entropic bonding is a way of explaining how nanoparticles interact to form crystal structures. It’s analogous to the chemical bonds formed by atoms. But unlike atoms, there aren’t electron interactions holding these nanoparticles together. Instead, the attraction arises because of entropy.

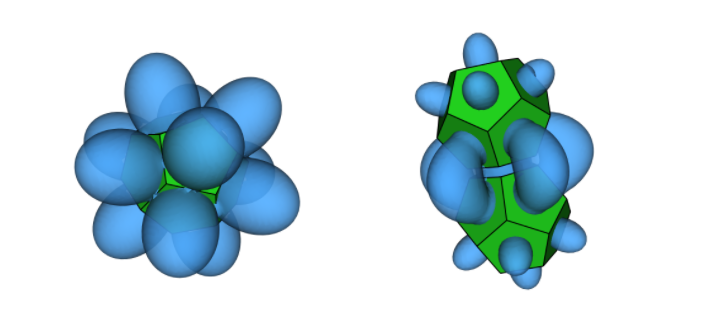

Oftentimes, entropy is associated with disorder, but it’s really about options. When nanoparticles are crowded together and options are limited, it turns out that the most likely arrangement of nanoparticles can be a particular crystal structure. That structure gives the system the most options, and thus the highest entropy. Large entropic forces arise when the particles become close to one another.

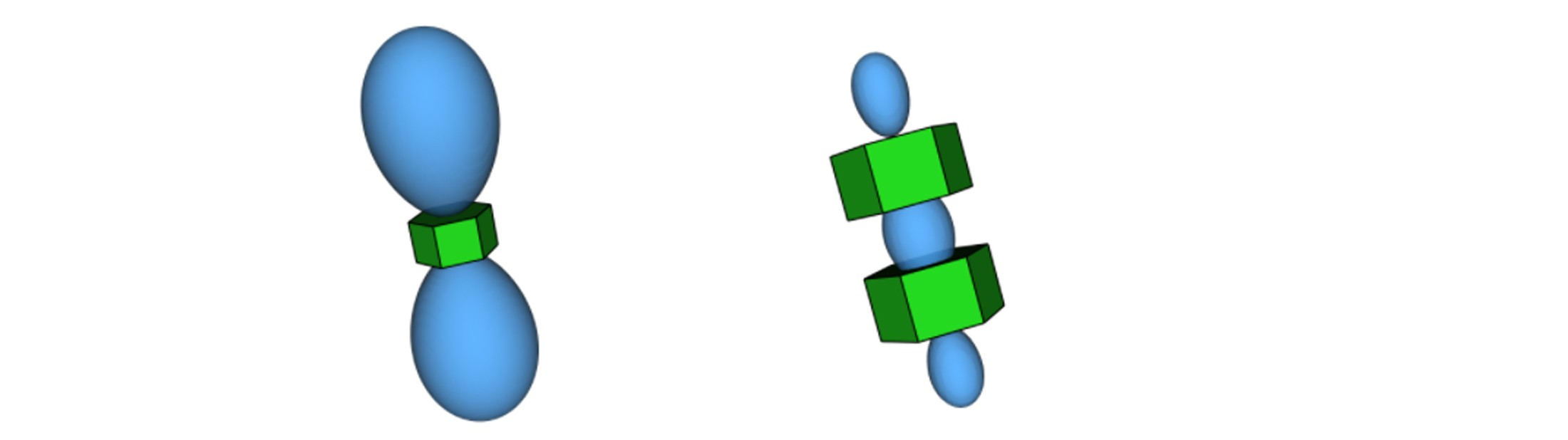

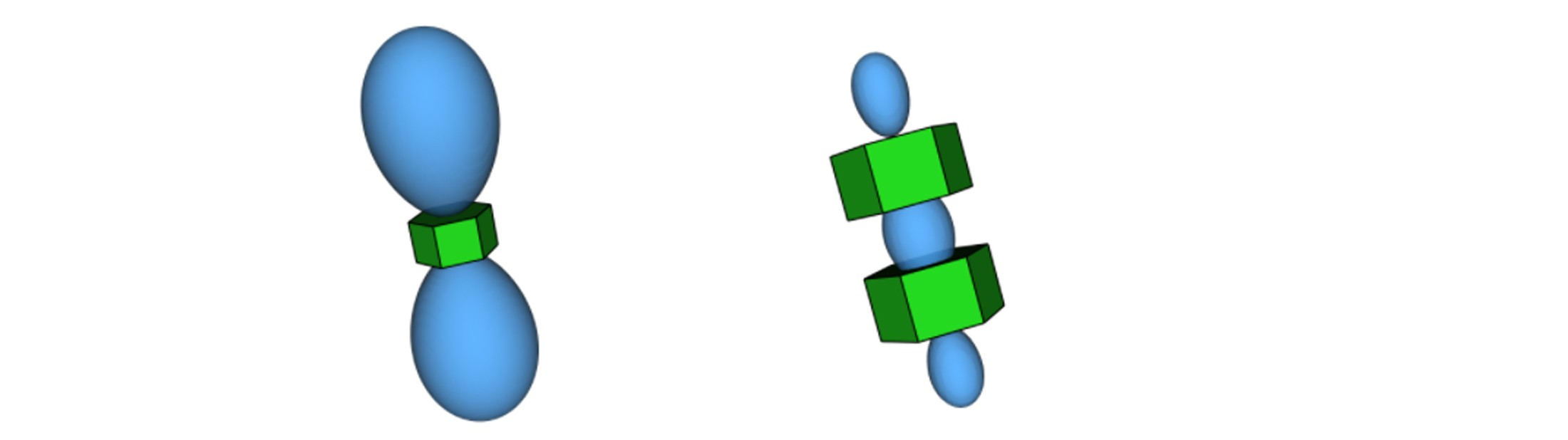

By doing the most extensive studies of particle shapes and the crystals they form, my group found that as you change the shape, you change the directionality of those entropic forces that guide the formation of these crystal structures. That directionality simulates a bond, and since it’s driven by entropy, we call it entropic bonding.

Why is this important?

Glotzer: Entropy’s contribution to creating order is often overlooked when designing nanoparticles for self-assembly, but that’s a mistake. If entropy is helping your system organize itself, you may not need to engineer explicit attraction between particles—for example, using DNA or other sticky molecules—with as strong an interaction as you thought. With our new theory, we can calculate the strength of those entropic bonds.

While we’ve known that entropic interactions can be directional like bonds, our breakthrough is that we can describe those bonds with a theory that line-for-line matches the theory that you would write down for electron interactions in actual chemical bonds. That’s profound. I’m amazed that it’s even possible to do that. Mathematically speaking, it puts chemical bonds and entropic bonds on the same footing. This is both fundamentally important for our understanding of matter and practically important for making new materials.

Electrons are the key to those chemical equations though. How did you do this when no particles mediate the interactions between your nanoparticles?

Glotzer: Entropy is related to the free space in the system, but for years I didn’t know how to count that space. Thi’s big insight was that we could count that space using fictitious point particles. And that gave us the mathematical analogue of the electrons.

Vo: The pseudoparticles move around the system and fill in the spaces that are hard for another nanoparticle to fill—we call this the excluded volume around each nanoparticle. As the nanoparticles become more ordered, the excluded volume around them becomes smaller, and the concentration of pseudoparticles in those regions increases. The entropic bonds are where that concentration is highest.

In crowded conditions, the entropy lost by increasing the order is outweighed by the entropy gained by shrinking the excluded volume. As a result, the configuration with the highest entropy will be the one where pseudoparticles occupy the least space.

The research is funded by the Simons Foundation, Office of Naval Research, and the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. It relied on the computing resources of the National Science Foundation’s Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment. Glotzer is also the John Werner Cahn Distinguished University Professor of Engineering, the Stuart W. Churchill Collegiate Professor of Chemical Engineering, and a professor of material science and engineering, macromolecular science and engineering, and physics at U-M.